New World Bank Report: Nigeria’s Exchange Rate Policies Fueling Inflation, Affecting Food Prices

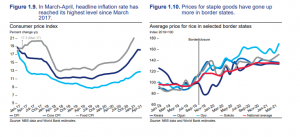

Nigeria’s use of multiple exchange rates regimes may have contributed to a rise in the country’s inflation rate, the latest World Bank report has said. In addition, the report says ongoing restrictions on the use and movement of foreign exchange are “further pushing up prices of food and agricultural inputs like fertilizer.”

Misaligned Exchange Rates

In a report that focuses on the country’s inflation trends, the global lender bemoans Nigeria’s reluctance to move the official exchange rates in tandem with the naira’s depreciation. The report explains:

Even though the nominal Investors and Exporters Foreign Exchange window [IEFX] exchange rate has been depreciating, which has helped to alleviate inflationary pressures, it has not been doing so fast enough to equilibrate the FX market.

As previously reported by Bitcoin.com News, Nigeria recently devalued the naira’s exchange rate to the current N411 for every US dollar. However, this new rate still falls short of the parallel market rate of over N490 for every dollar.

It is this disequilibrium between the official and the parallel market rates which the World Bank blames for helping cause an upswing in inflationary pressures. The report continues:

“When there is a divergence between the official/IEFX rate and the parallel FX rate, the parallel rate is the one most associated with food price dynamics. Unable to access FX in the IEFX window, businesses seek it through the parallel market and other alternative sources and factor in the parallel rate in business decisions, so that it eventually passes through to market prices for goods and services.”

Inconsistent CBN Policies Attacked

The same report also cites the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN)’s monetary policy which it says is “not consistent with prioritizing efforts to curb inflation.” The report asserts that the tools used by the CBN to achieve its policy goals “sometimes contradict each other.” For example, keeping the exchange rate stable or fixed promotes growth and helps to contain inflation. However, the same policy weakens the effectiveness of monetary transmission mechanisms to contain inflationary pressures.

Meanwhile, the World Bank (as part of its many recommendations) wants the West Africa country to make the Nigeria Autonomous Foreign Exchange (NAFEX) exchange rate — now the anchor rate for all formal foreign exchange transactions — more flexible in order to reduce real exchange rate misalignments. A more flexible rate could also boost Nigeria’s competitiveness, and narrow the spread between the NAFEX rate and the parallel market rate, with a positive effect on inflation dynamics.

Do you believe that it is still possible for Nigeria to significantly narrow the official and parallel market exchange rates? Tell us what you think in the comments section below.